Did the Quran Reveal What Others Missed?

Hieroglyphics and the Test of Scriptures

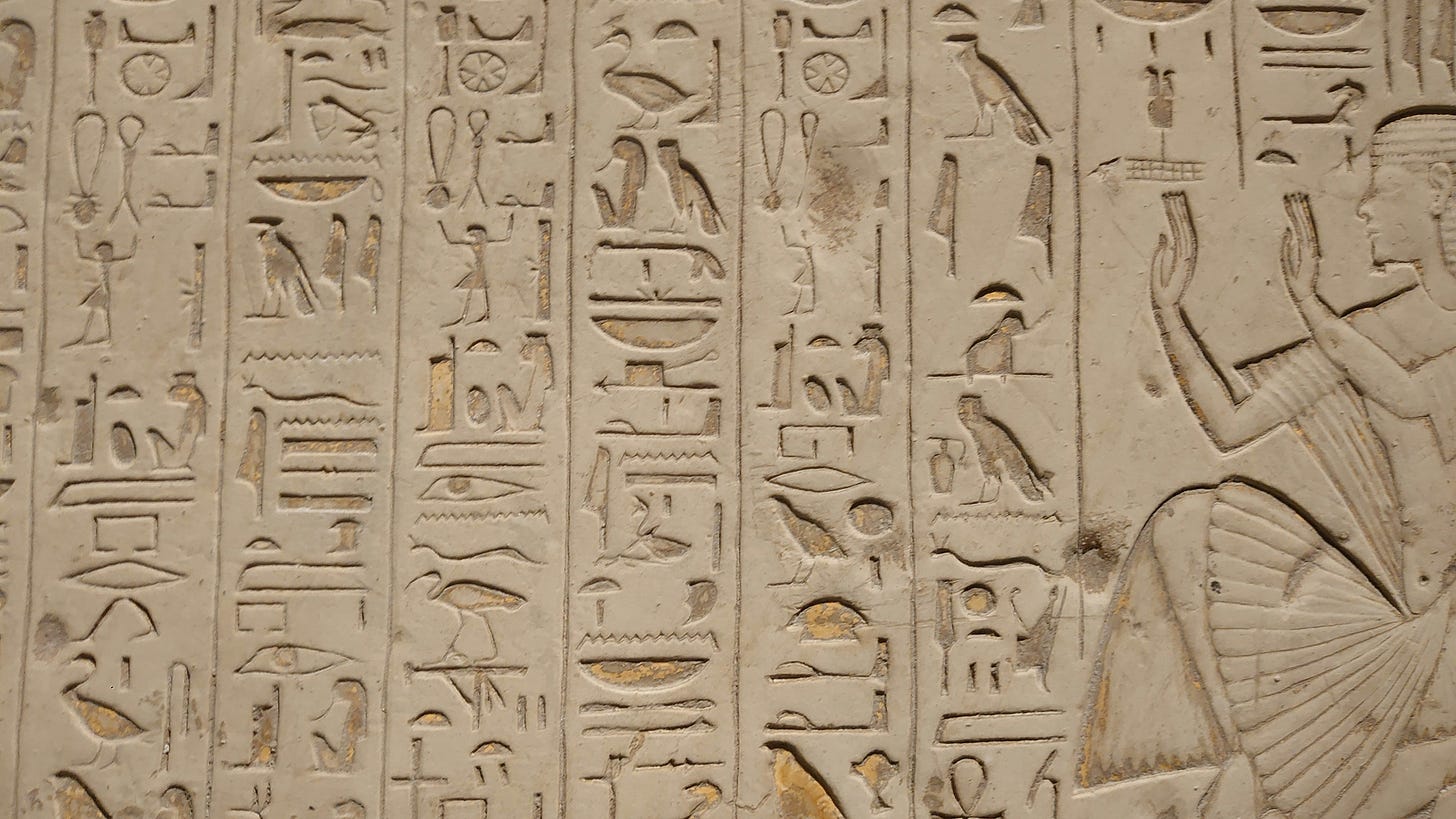

Introduction to Hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphics was a system of writing used by ancient Egyptians, represented by symbols that conveyed sounds, words, or ideas. The word "Hieroglyphics" comes from the Greek terms hieros (sacred) and glyphe (carving), meaning "sacred engraving." This script, introduced around 3,300 BC, was employed in temples, tombs, statues, scrolls, and other inscriptions to record Egypt's history, religion, and governance.

While hieroglyphics remained central to Egyptian life for millennia, the subsequent shifts in regional power began to impact the script's usage.

The use of hieroglyphics began to decline as Egypt was invaded by powerful empires, such as the Persian Empire (in 525 BC), and then the Kingdom of Macedonia (in 332 BC), followed by the Roman Empire (in 30 BC).

These foreign invasions brought cultural, linguistic, and religious changes that heavily impacted Egypt’s native traditions. The Romans, with Greek and Latin as their official languages, played a major role in the decline of hieroglyphic writing. By the 4th century AD, when Rome adopted Christianity as its official religion, hieroglyphs were not only overshadowed by the new language but were also banned in religious contexts. Temples were destroyed, and the script was soon forgotten, known only to a few priests and scholars. Hieroglyphics gradually fell into disuse and became incomprehensible.

In 1799, during a military expedition led by French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte in Egypt, an engineering officer named Pierre Bouchard discovered a black granite slab while constructing a fortress near Rosetta in northern Egypt. This slab, later known as the Rosetta Stone, was inscribed with three scripts:

Hieroglyphics — the sacred script of ancient Egypt

Demotic — the everyday script of ancient Egyptians

Greek — the language of the ruling class at the time

The Rosetta Stone, found and dated to 196 BC, turned out to be the key to cracking the code of this lost language. The same text was written in all three scripts, making the stone a key to understanding ancient Egyptian writing.

While the stone offered a key, the complexity of the ancient language still posed a significant challenge. Hundreds of scholars attempted to decode the hieroglyphs, but it wasn't until 1822—23 years after its discovery—that French linguist Jean-François Champollion successfully deciphered the hieroglyphs using the Greek text. This breakthrough revolutionised the study of ancient Egypt and laid the foundation for modern Egyptology.

Given this historical overview, we now consider how the Qur’an addresses information that remained hidden for a long period, and was eventually understood."

The Test of Scriptures: The Qur’an as Muhaymin

The Qur’an describes itself as Muhaymin over previous scriptures, meaning it acts as a guardian, preserver, and criterion for distinguishing truth from distortion. Rather than replacing earlier revelations, the Qur’an confirms the original divine messages while correcting the alterations made over time (Bucaille, 1976). It provides an unaltered standard, ensuring that God's guidance remains intact and accessible to all people, across all eras (Nasr, 2015).

When we consider modern-day discoveries, Muhaymin becomes especially significant, particularly when examining religious texts. The Qur’an asserts that while previous scriptures originated from divine revelation, they have been altered through human interference.

Elaboration on "Muhaymin"

The Qur'anic term Muhaymin carries significant theological weight and is central to understanding the Qur'an's relationship with previous scriptures. While often translated as "guardian" or "preserver", its implications extend beyond these terms.

The root of "Muhaymin" suggests a multifaceted role involving:

Oversight and Supervision: It implies a position of authority and control, in which the Qur'an oversees and judges the authenticity of earlier revelations.

Protection and Preservation: "It signifies a safeguarding of the original divine message, protecting it from distortions and alterations that may have occurred over time.

Criterion and Standard: It establishes the Qur'an as a benchmark against which the truth and accuracy of previous scriptures can be measured.

Furthermore, the concept of "Muhaymin" implies a continuity of divine guidance, suggesting that God's message remains relevant and accessible to all people, across all eras. It reinforces the idea that the Qur'an is not a replacement for earlier scriptures but a culmination and completion of them.

Understanding the multifaceted nature of "Muhaymin" is crucial for understanding the Qur'an's claims regarding its relationship with the Torah and the Gospels. It provides a framework for evaluating the Qur'an's assertions of accuracy.

The Qur’an’s assertions in reference to Muhaymin can be tested through historical, linguistic, and archaeological findings. But does the Qur'an’s claim as 'Muhaymin' hold up against historical scrutiny? Let’s put it to the test.

1 - The Weeping of the Skies for Pharaoh

Ancient Egyptian texts, including the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, suggest that the heavens and earth mourned the death of great rulers, particularly Pharaohs (Allen, 2000). These inscriptions describe the sky shedding tears for the deceased king—a belief confirmed by Egyptologist James Allen through hieroglyphic records.

However, the Qur’an directly refutes this notion, stating:

”Neither the heavens nor the earth wept for them, nor were they reprieved." (Qur’an 44:29)

This verse challenges the Egyptian worldview, rejecting the idea that Pharaoh's death was a cosmic event worthy of grief. Instead, it portrays his downfall as one of disgrace, and not divine mourning.

A Belief Unknown to Arabia

The most striking aspect of this Qur’anic statement is that the idea of the heavens weeping for Pharaoh remained virtually unknown for centuries. Consider the following:

The Bible makes no mention of the heavens or earth mourning Pharaoh's death.

Arab traditions had no recorded knowledge of this ancient Egyptian belief.

Hieroglyphics remained undeciphered until the 19th century—long after the Qur’an’s revelation.

Why is this significant? The Qur’an does not merely omit or ignore this Egyptian belief—it actively negates it, correcting an idea that was only rediscovered after the deciphering of hieroglyphics. This raises a profound question: If the Qur’an had been derived from earlier scriptures, why would it uniquely refute a belief that neither the Bible nor any other source contained?

Furthermore, the Qur'an's precision extends beyond challenging existing beliefs, to the very terminology it uses in its historical accounts. Thus, the Qur’an not only rejects a belief lost to time but does so with precision that aligns with rediscovered hieroglyphic records.

2 - Chronological Terminology in the Qur'an and Historical Records

The Qur’an's accuracy in distinguishing the titles of Egyptian rulers is a fascinating example of its historical precision. While the Bible consistently refers to the Egyptian ruler as "Pharaoh" in both periods (e.g., Genesis 41:14, 41:39-41, 47:5-6), the Qur’an makes a distinction between the two periods. It refers to the ruler in Joseph's time as "King" (Malik) (e.g., 12:54), and the ruler in Moses’ time as "Pharaoh" (Fir'awn) (e.g., 28:38, 7:103) (Kitchen, 2003).

This distinction holds significant historical importance, only confirmed by modern Egyptology after the deciphering of hieroglyphics in the 19th century (Finkelstein & Silberman, 2001).

Confirmation from Hieroglyphics

For centuries, it was unknown that the title "Pharaoh" was not used for Egyptian rulers in all periods. The discovery and deciphering of hieroglyphics revealed that the term "Pharaoh" was not used for Egyptian rulers during Prophet Joseph’s era (Middle Kingdom, approximately 2000–1700 BCE). The title "Pharaoh" became common only in the New Kingdom (around 1500 BCE), which corresponds to Moses’ time. Ancient Egyptian inscriptions confirm that rulers in Joseph’s period were called "King," and not "Pharaoh."

A Comparison of Terminology

No historical records available in Arabia at the time contained this distinction. The Bible, which was accessible to Arabian Jews and Christians, consistently used "Pharaoh" for all Egyptian rulers, making the Qur’an’s differentiation even more remarkable.

This level of accuracy raises profound questions. Could someone as far back as the 7th century, without access to historical Egyptian records or the ability to read hieroglyphics, have highlighted such a distinction purely by chance? Had the Qur'an been influenced by existing scriptures, it would have inherited the same error. Instead, it stands apart, using terminology only confirmed centuries later.

3 - Haman: The Chief of Construction under Pharaoh

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur’an (Surah 28:6, 8, 38; Surah 29:39; Surah 40:24, 36) as a high-ranking official under Pharaoh, overseeing major construction projects. Surah Al-Qasas records Pharaoh commanding him:

“O Chiefs! I know of no other god for you but myself. So, bake bricks out of clay for me, O Haman, and build a high tower so I may look at the god of Moses, although I am sure he is a liar.”

(Qur’an 28:38)

For centuries, critics argued that the Qur’anic mention of Haman was an anachronism, pointing out that no such figure appeared in historical records of ancient Egypt. The only known "Haman" in religious texts was from the Book of Esther, set in Persia nearly a thousand years after the time of Moses. This led some Western scholars to claim that Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) had mistakenly borrowed the name from Biblical sources.

The Rediscovery of Haman

This criticism persisted until the deciphering of hieroglyphics in the 19th century. In 1935, German Egyptologist Hermann Ranke, in his work Die Ägyptischen Personennamen (The Egyptian Personal Names), documented a name phonetically similar to "Haman" in inscriptions dating to the New Kingdom period (circa 1550–1070 BCE). This individual was associated with construction projects, aligning perfectly with the Qur’anic description.

Further supporting evidence emerged from artifacts housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. One such artifact is a doorpost from the tomb of Hemen-hetep, who held the title "Overseer of the Stonemasons of Amun." This artifact dates to the New Kingdom, the period traditionally associated with Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE), often identified as the Pharaoh of Moses.

Maurice Bucaille on ‘Haman’

Maurice Bucaille, in The Bible, The Qur’an, and Science (Bucaille, 1976), discusses this discovery, noting that the Qur’an correctly places Haman in an Egyptian context rather than in Persia, where the Biblical Haman appears. Bucaille emphasised that it is extraordinary that the Qur’an mentions such an obscure historical figure, who was unknown in the Torah and other sources available in 7th-century Arabia (Ranke, 1935). He saw this as evidence of the Qur’an’s historical accuracy, challenging conventional explanations of its origins.

This raises an intriguing question: How did the Qur'an accurately identify an obscure figure and his role—something unknown even to the Jews and Christians of that time?

Apart from discoveries clearly validated by hieroglyphics, there are other remarkable findings that, while exhibiting indirect support from hieroglyphic texts, strikingly align with historical reality. Below, I present two such examples.

4 - The Case of Brick-Making in Ancient Egypt

Another instance where the Qur’an could have erred, but did not, is in its mention of brick-making in ancient Egypt.

The Qur’an narrates Pharaoh instructing Haman:

“So kindle for me, O Haman, a fire on the clay and build for me a tower…” (Qur’an 28:38)

This verse references the process of baking bricks, which, at first glance, may seem more characteristic of Mesopotamian architecture than Egyptian. Ancient Egypt predominantly used sun-dried mud bricks for construction. However, archaeological discoveries have shown that kiln-fired bricks were indeed used in Egypt, particularly during later periods (Parker, 2015; Lehner, 1997).

It is noteworthy that the Qur’an reflects a practice that would only be confirmed by archaeology centuries later. It shows a precise understanding of historical practices that was unknown at the time.

These examples demonstrate that the Qur'an presents details that align with later historical discoveries. Far from borrowing from contemporary sources, its descriptions are consistent with later discoveries, or at the very least, free from the historical errors known to us today.

5. The Preservation of Pharaoh’s Body

The Qur’an states:

"So today We will save your body so that you may be a sign for those after you. But most people are heedless of Our signs."

(Qur’an: 10:92)

For centuries, scholars debated the meaning of this verse, as there was no known record of a Pharaoh's body being preserved after drowning. However, with the 19th-century rediscovery of hieroglyphics and advancements in Egyptology, the mummies of several New Kingdom rulers, including Merneptah, were found and analysed.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions confirm that Pharaohs underwent elaborate mummification processes, but they do not describe the preservation of a drowned ruler. However, forensic studies of Merneptah’s mummy—which was discovered in 1898 in the Royal Cache at Deir el-Bahari—suggest unusual damage to his body. Some researchers, including Dr. Maurice Bucaille, have argued that his remains exhibit characteristics consistent with rapid death, possibly due to drowning, followed by mummification.

Key observations include:

Well-Preserved Mummy – Despite significant damage to the body, the mummy was well-preserved, aligning with the Qur'anic claim that his body was saved as a sign.

Possible Asphyxiation Indicators – Forensic analyses conducted on the mummy suggest that his posture and physical condition could be consistent with drowning.

Non-Battle Wounds – Unlike Pharaohs who died in battle, Merneptah’s body does not show injuries typically associated with warfare, which raises questions about the cause of his death.

Though hieroglyphic records meticulously document mummification, they remain silent on the preservation of a drowned Pharaoh. The Qur'an's specific claim, therefore, stands out as exceptionally remarkable.

Conclusion

In the modern era, a wealth of discoveries—from ancient manuscripts to archaeological findings—has illuminated details within the Qur’an, particularly regarding ancient civilisations, lost knowledge, and prophetic narratives. The deciphering of hieroglyphics, for instance, has revealed historical facts about ancient Egypt that align with certain Qur’anic accounts, such as the references to 'Haman' and the descriptions of construction practices like brick-making. These facts, confirmed only after the rediscovery of hieroglyphics, present intriguing points of comparison with modern archaeological and historical discoveries.

Bibliography

Bucaille, M. (1976). The Bible, the Qur’an, and science: The Holy Scriptures in the light of modern knowledge. Islamic Book Trust.

Lehner, M. (1997). The complete pyramids: Solving the mysteries of the world's largest buildings. Thames & Hudson.

Nasr, S. H., Dagli, M. F., Dakake, M. M., Lumbard, J. E. B., & Rustom, D. (Eds.). (2015). The study Quran: A new translation and commentary. HarperOne.

Parker, R. A. (2015). The archaeology of ancient Egypt: An introduction. Routledge.

Ranke, H. (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen (The Egyptian personal names). Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.

Recommended Reading: